Sow Bug vs. Pill Bug

Sow bugs are land crustaceans and look very similar to pill bugs, at least at first glance. Sow bugs are small crustaceans with oval bodies when viewed from above, their back consists of a number of overlapping, articulating plates. They have seven pairs of legs, and antennae which reach about half the body length. Most are slate gray in colour and may reach 15 mm long and 8 mm wide.

The pill bug on the other hand has a rounder back from side to side, and a deeper body from back to legs. When disturbed, it frequently rolls into a tight ball with its legs tucked inside, much like its larger but dissimilar counterpart, the armadillo.

Sow bugs have gills which need constant moisture, so they tend to live in moister northwest climates. They are primarily nocturnal and eat decaying leaf litter and vegetable matter. They may feed on the tips of young plants, so can be considered pests, but they also help the environment by breaking up decaying plant matter, helping speed up the recycling of the nutrients contained there.

Control

Control

The presence of sow bugs or pill bugs in the living quarters of a home is an indication of high-moisture conditions. This condition will also contribute to a number of other problems including mildew, wood rot and a good breeding environment for other insects. Reduce moisture or humidity level indoors. Use bathroom fans, stove hood vent fans, vent clothes dryers outside. Crawl spaces and attics need to be well ventilated. Remove excess vegetation and debris around exterior perimeter of the home. Make sure that leaf debris (leaves hold moisture and hide the bugs) is cleaned up from around the outside of your house. Keep rain gutters and downspouts clean and in good repair. Instead of chemicals, use caulking to close any cracks or crevices at or near ground level.

Houses built on a concrete slab poured directly on the ground can have more of a problem with sow bugs or pill bugs – if there is no moisture barrier under the concrete. Built-in planters are usually a bad idea for many reasons. Window box planters and planter boxes on decks tight against the house are good breeding places for many bugs. Make sure all your doors (ground level, to the outside) are weather-stripped. If your garage is attached or integral with the house, make sure those doors are properly weather-stripped also. Watch for obvious moisture problems in the garage and bottom level. Keep soil levels well below structural wood around the home.

Root Weevil

Root weevils are common invaders of Kootenay homes. Although a nuisance, they cause no harm to humans, pets or household furnishings.

Life Cycle and Habits

The black vine and strawberry root weevil have similar life cycles and are the most common in BC.

Root weevils wander into homes most frequently during late June and July. Household migrations greatly increase during periods of hot, dry weather. The insects apparently are attracted to the moisture of the building. Inside homes, the root weevils cause no injury to humans or household furnishings, they can, however, be quite abundant and a considerable nuisance.

Exactly why these insects are attracted to homes is unclear, perhaps houses provide shelter during the hot summer months when the insects are relatively inactive. Moisture sources in and around homes also attract the adult weevils.

Control

Control

Because root weevils do no harm inside homes, the best way to handle infestations is to tolerate occasional beetles, vacuuming them as they are observed. However, if greater numbers are observed, a treatment can reduce the amount of activity. For more information regarding a treatment, please call us anytime.

Control also includes sealing openings and screening windows to prevent entry. Root weevil populations can be reduced by removing plants around the outside of the home on which the insects feed. These especially include Rhododendrons and Yews (or Taxus). Reducing watering around building foundations may limit root weevil migrations, as the adult insects appear attracted to shade and moisture.

Black Vine Weevil

Black Vine Weevil

One of several types of root feeding weevils, the black vine weevil is the most destructive and widespread. A European native, it was most likely introduced accidentally in plant materials. Though first reported in 1910 in Connecticut, researchers suspect that it was introduced in the 1830s.

This weevil has spread by the movement of ornamental plants and thus is found throughout most of Canada. Facilitating its wide geographic range may be its rather flexible choice of foods—it feeds on over 100 types of plants, trees, shrubs and flowers.

Cluster Fly

Although the cluster fly is a nuisance pest for homeowners, they do not bite people, carry diseases, nor cause any real damage to a home. Cluster flies are about five-sixteenths of an inch long; they are gray with golden-toned hairs on their thorax.

Spotting them is easy because they are usually clustered together sunning themselves on exterior walls. This is also where their name comes from because when resting, they generally cluster together.

The cluster flies are similar to many other pests as they want to get inside houses to stay warm. With this in mind, the winter is when people will most often find cluster flies inside their homes.

Habits and Breeding

Habits and Breeding

Cluster flies search for any small openings that will get them into a house; open windows or doors are great opportunity. They generally enter homes in the fall, as the weather begins to cool down.

By winter, most cluster flies will be hibernating within a warm home. While hibernating the cluster fly is not very active, so a homeowner might not even know they are there – although there are occasions where the cluster flies will come out in to sun themselves – a lovely, warm and south facing window is where a homeowner is likely to spot them, otherwise they pretty much stay in hibernation.

Also known as an attic fly, Cluster flies like to hibernate in – you guessed it – attics and wall voids. They like to be higher off the ground and will cluster together once in hibernation.

Once spring starts, the cluster flies will leave the house and venture back outside where they will mate and eat, neither of which they do during hibernation.

The cluster fly reproduces frequently. Females don’t to do much: once they have mated they lay their eggs in soil near earthworms. About three days later the eggs will hatch and the larvae will migrate towards the earthworms, burrowing inside and using the earthworm as a food source. Once fully developed, the cluster fly will be on its own. This cycle will continue from the spring to the summer, during which four generations or more can be made. As summer comes to an end and fall approaches the cluster flies begin to look for another home, or the same home, to hibernate in.

Earwig

The name “earwig” comes from an old superstition that these insects crawl into the ears of sleeping people, doing predictably nasty damage. This is not one of their behaviors, of course, but because earwigs do hide in crevices and crannies, they may inadvertently and rarely enter the ears of people lying on the ground. Presumably, many different kinds of small invertebrates could also do this.

Habits

Habits

Earwigs forage mainly at night, and during the day conceal themselves in all sorts of enclosed spaces: under stones, wood and bark, in vegetation and flowers. Even those species able to fly seldom seem to do so.

The 1350 species of earwigs in the nine families of the Order Dermaptera are mostly tropical in distribution. Some species are native in temperate regions, but few can tolerate cold winters and all the species recorded in BC were introduced from other lands. The random, alien origin of our earwigs is reflected in the diversity of the small fauna – four species in four genera and three families. Like cockroaches, earwigs are secretive and omnivorous, two characteristics that make them successful hitchhikers with human travelers – some kinds have become cosmopolitan.

Unlike cockroaches, most of these successful immigrants have established themselves out-of-doors and are not normally pests of human habitations. In Canada, because of their foreign origins and dislike of the cold, most species are concentrated on the coasts and in the Great Lakes region. They tend to live in disturbed habitats, on beaches and around gardens and human habitations.

Most species are omnivorous scavengers although some are known to be exclusively predaceous; in coastal BC for example, Anisolabis maritima (Bonelli) evidently feeds mainly on invertebrates found on ocean beaches. Forficula auricularia Linnaeus, when abundant, can be a pest of garden plants, and is especially fond of flowers. In general, earwigs probably cause serious damage to plants only when insect prey is limited. Prey can be captured with the forceps, although these are also used in courtship and probably mostly in defence: the larger species can give a human finger a painful pinch.

Eggs are laid in underground burrows, usually in batches of 20 to 40. Females of some species, including the widespread Forficula auricularia, guard the eggs and show some care and protection of their young. Family groups often remain associated and semisocial behaviour occurs. Nymphs usually moult four to six times.

Description

The earwig body is small- to moderately-sized (5 to 30 mm long, although some foreign species may reach 5 cm), slender, elongated and rather flattened. The mouth parts are made for chewing and the antennae are filamentous, usually less than half the body length. There are no ocelli. Legs are similar in size and form; the tarsi have three segments. Wings are often absent. When present, the forewings are modified into short, rectangular, vein-less, leathery flaps. Hind wings may be absent even if the forewings are developed, but when present, are usually semicircular and pleated, with radiating veins. Each is stowed as a folded packet under the much smaller forewings, and the tips often project from beneath. The paired cerci at the tip of the abdomen are usually unsegmented, and strongly sclerotized into forceps. These pincers, which are the most familiar feature of the order, are usually stronger and more curved in males. The females, except in some primitive species, lack an ovipositor.

To control the number of earwigs in and around the house:

- Reduce lighting on the outside of the house

- Eliminate damp, moist conditions in crawl spaces under houses, around faucets, around air-conditioning units and along foundations

- Be sure rain gutters are carrying water away from the house and foundation

- Use caulking, putty and weather stripping around doors, windows and other entry sites

- Be sure the landscaping creates a clean, dry border immediately around the foundation wall. For example, use gravel or ornamental stones rather than flower beds or mulch along the walls.

Hobo Spider

Tegenaria Agrestis, better known as the hobo spider, is a recently introduced species to the United States and Canada, coming from Europe to the Pacific Northwest.

Hobo spiders have been labeled as spiders of medical importance because of the belief that their bites can cause severe pain and potentially necrotic wounds. The research, however, on hobo spider bites is incomplete with no definitive answer regarding their level of danger to humans.

Most experts warn against using a single picture for any conclusive spider identification, including the hobo. Given that fact, the picture here shows a spider that has many of the hobo spider’s physical characteristics. There are no bands on the legs and the abdomen has a “v” pattern down the middle.

Compare the picture to the left with the picture below of the giant house spider, another Tegenaria species. The slight differences in the colour of the abdomen and cephalothorax provide another comparative identification clue.

The hobo spider belongs to the funnel web spider family (Agelenidae), the two spinnerets extending from the bottom of the abdomen being characteristic of the species.

Like other funnel web spiders, they prefer the outdoors and tend to only come indoors during the late fall, as the season changes. Wandering males also are known to meander through a house.

Persons suspecting they have been bitten by a hobo spider should seek medical attention. If circumstances permit, trapping the spider for positive identification helps with diagnosis and treatment.

At one time or another, many different spider species – from jumping spiders to cellar spiders to wolf spiders and more – find their way into people’s homes.

Technically, the term house spider refers to species in the Tegenaria genus, with three species commonly found in Canada:

- Tegenaria agrestis – hobo spider

- Tegenaria domestica – domestic or common house spider

- Tegenaria gigantea – giant house spider

The three species look very similar, with the hobo spider commonly considered a species of medical concern. The range of the hobo spider and giant house spider are limited mainly to the Pacific Northwest, although extended ranges to Utah, Montana and the interior BC are reported.

While giant house spiders are large, up to 3” long with their legs extended, their bites are not as dangerous as the hobo spider. In fact, they are a natural predator of the hobo spider and their presence is considered a natural pest management remedy.

Indian Meal Moth

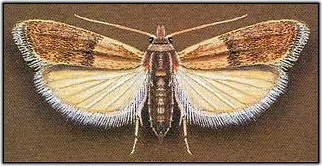

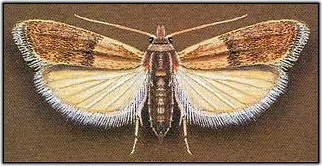

The Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella (Hubner), is one of the most commonly reported pests of stored grains in Canada.

Larvae of the Indian meal moth feed upon grains, grain products, dried fruits, nuts, cereals and a variety of processed food products. The Indian meal moth is also a common pantry pest.

The Indian meal moth is handsome with a wing expanse of nearly three-quarters of an inch. It is easy to distinguish from other grain pests by the peculiar markings of the forewings: they are reddish brown with a copper luster on the outer two-thirds and whitish gray on the inner, or body ends. The hind wings lack distinctive markings and are more or less uniformly gray. Adults can be seen resting on the grain surface or grain bin walls. The adults fly at night and are attracted to lights.

The eggs of the Indian meal moth are whitish, ovate and very small. making them difficult to see without the aid of a microscope.

Newly hatched larvae are also very small and difficult to see. Larger larvae are usually yellowish, greenish or pinkish in colour. Fully grown larvae are a half to five-eighths of an inch in length with a brownish head capsule. Larvae have three sets of legs near the head (thoracic legs) and five sets of prolegs on the abdomen. Larvae of the meal moth spin a web as they become fully grown and leave behind silken threads wherever they crawl. This loosely clinging webbing on the grain is characteristic of this pest and often abundant enough to attract attention.

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

As long as the temperature within a grain bin or building where grain is stored remains above 50° F (10° C), the Indian meal moth can survive and reproduce. A typical life cycle (egg to adult) is completed in forty to 55 days with the potential for seven to nine generations per year, however, because of cooler temperatures during the winter months, fewer generations are produced. Under optimal conditions, the entire life cycle can be completed in approximately 28 days.

A mature female lays 100 to 300 eggs on food material, either singularly or in groups of twelve to thirty. Larvae begin to hatch in two to fourteen days, depending on environmental conditions. Newly hatched larvae feed on fine materials within the grain and are small enough to pass through a 60-mesh screen making it difficult to exclude larvae from most packaged foods and grain.

Silverfish

Silverfish are silvery to brown in colour because their bodies are covered with fine scales. They are always wingless and generally soft-bodied. Adults are up to three-quarters of an inch long, flattened from top to bottom, elongated and oval in shape, have three long tail projections and two long antennae.

The Firebrat, Thermobia domestica (Packard), is quite similar in habits but is generally darker in colour. The firebrat prefers temperatures over 90°F (32° C) but has a similar high humidity requirement so it is commonly found near heating pipes, fire places, ovens and other heat sources.

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

Silverfish have a simple metamorphosis (egg – nymph – adult) with females laying eggs continuously after reaching the adult stage. She may lay over 100 eggs during her life which are deposited singly or in small groups in cracks and crevices. Hatching in three weeks, Silverfish develop from egg to young to adult within four to six weeks and continue to molt throughout their life. Immature stages appear similar to adults except they are about one-twentieth of an inch long and when they first hatch are whitish in colour, taking on the adults’ silver colouring as they grow. They are long- lived, surviving from two to eight years.

Habitat and Food Sources

Silverfish are chewing insects and general feeders, preferring carbohydrates and protein, including flour, dried meat, rolled oats, paper and even glue. They can survive long periods without food – sometimes over a year – and are sensitive to moisture. requiring high humidity (75% to 90%) to survive. Silverfish have a temperature range between 70°F and 80°F (21° C to 26° C). They are fast running and mostly active at night, generally tending to reside in the lower levels of homes although have been found in attics.

Pest Status and Damage

Pest Status and Damage

Silverfish are medically harmless and primarily a nuisance pest inside the home or buildings: they can contaminate food, damage paper goods and stain clothing. Many of their habits are similar to cockroaches and they appear to be more a common household pest in drier parts. They can occasionally damage book bindings, curtains and wallpaper.

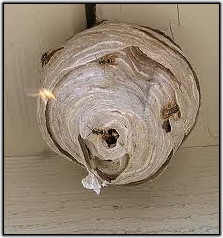

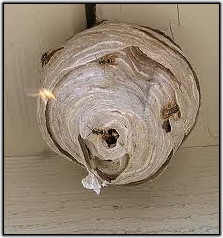

Wasp

The wasps that are known as “yellow jackets” and “hornets” are medium-sized insect pests 10 to 25 mm long, easily recognized by the bands of black and yellow or white on their stomachs. There are, however, many other types of harmless wasps that look similar and can be mistaken for pests.

A hollow stinger, found at the rear of the wasp’s body, injects venom when it penetrates the skin. These stings can be quite painful.

The species known as social wasps are the most common and also the most dangerous because of their behaviour; among them, German yellow jackets are considered the most aggressive. Social wasps make paper nests in different shapes and sizes, some quite visible and others hidden: the nest can be fully enclosed with an opening near the base or it can be an open structure, depending on wasp species.

In early spring, the hibernating queen comes out of her crack, crevice or tree bark to look for a new nesting site. Once found, she builds the first few paper cells and lays a single egg in each cell. After being nurtured by the queen, these new workers will take over all the colony duties like feeding and tending the queen, tending the new larvae, hunting and scavenging for food, building new brooding cells, and cooling the nest on hot summer days. The queen’s sole role is then to lay eggs for the rest of summer.

All larvae become female workers, except in late summer where some of the eggs hatch into the reproductive males and females that will produce the next season’s generation. Only the inseminated females survive the winter to start the cycle again as new queens; all workers and the old queen die and the nest is not used the following year.

What Can They Do?

What Can They Do?

Social wasps are common in urban and rural areas throughout North America and are the most common stinging menace in many Canadian cities.

Outdoor gatherings are often visited by wasps because of their attraction to sweet foods and, earlier in the season, to food rich in protein. Stings can happen when people or animals bother wasps that are hunting for food or when a nest is approached by accident, triggering a defensive reaction from “guard” wasps. However, people or animals have been attacked even when seemingly unprovoked.

Thousands of people are stung by these venomous insects each year. In some rare cases, severe allergic reactions to the venom results in death. Immediate medical attention is required if a reaction to a sting includes unusual swelling, itching, dizziness or shortness of breath.

Unlike the bee, a wasp can sting more than once. Wasps can also damage ripe fruit by creating holes when they eat the flesh. Many species are known to habitually scavenge in city garbage bins.

However bothersome, wasps are beneficial in many ways. Workers catch insects like flies and caterpillars, carrying them back to the nest to feed the developing larvae. They also act as pollinators when they visit flowers for nectar. They are also a source of food for small mammals, birds and spiders.

Management Strategies

Management Strategies

Given their beneficial role in nature, tolerance is best for small populations of wasps. Learning to tell the difference between harmful social wasps and the solitary, harmless species prevents accidental exterminations and allows the solitary species to continue their valuable behavior.

Prevention

Inspect your yard and home surroundings in early summer, looking for any wasp activity or paper nests taking shape. It is easier to discourage a single queen wasp from establishing too close to your home than handle a full-size nest later in the season.

Physical Control

Since wasps hunt for high-protein food like insects to feed their larvae, make sure moist pet food or picnic leftovers are not left in the open. Other attractants like sweet food and strong scents like perfume and hair spray should be avoided and try not to leave food or drink uncovered when eating outside. Keep all garbage covered in tightly closed containers and walking barefoot on lawns or other grassy areas should not be encouraged, especially in late summer when wasps are more abundant and active.

Traps

Commercial traps are available at Cranbrook Pest Control

Traps

Commercial traps are available at Cranbrook Pest Control. Food bait can be used with these traps to increase their effectiveness. Be aware that there may be more wasp activity around baited traps, so they should not be placed close to play areas or other places of human activity. These traps can be useful in the short term during outdoor events where wasps can be drawn away from food-serving areas.

If the location of the nest does not present a health hazard, it’s best to leave it in place until November or December. Once the nest has been abandoned, the trap can be removed and the nest disposed of with minimal risk.

If the nest must be removed during the summer months, it should be done in the evening when wasps are least active. Nest removal can be dangerous and extreme caution must be used because of the risk of attack by a large group of wasps.

Depending on the location and structure of the nest, removal can be as simple as enclosing the nest in a plastic bag and detaching the single anchoring stalk from the supporting tree branch or structure. To dispose of the active nest, place in a freezer for at least 48 hours. Remember to always wear protective clothing, including a head net. Although a homeowner—with adequate protection—can remove a nest, professional help is recommended.

Products

Products

Treating the nest with an insecticide like pyrethrins is an effective way to control wasps. Spraying after nightfall is recommended because wasps are not considered nocturnal. Use a red filter over a flashlight for visibility instead of direct light as this will alarm the wasps and increase their activity. Always wear protective clothing when using pesticides.

What to Do if You are Stung by a Wasp

If a wasp lands on you, remain calm and wait for it to fly away or gently brush it off; sudden movements can cause the wasp to sting defensively. Stings can be soothed with ice packs or with a baking soda paste. A wasp’s venom is very potent and people with anaphylactic allergic reactions need medical attention immediately – even with the use of an anti-venom shot.

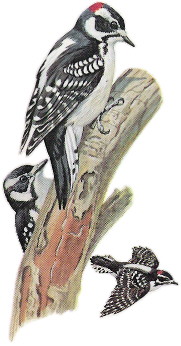

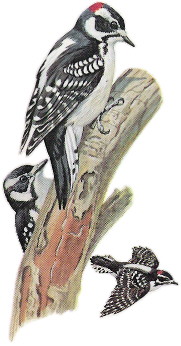

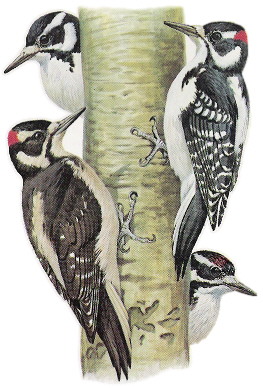

Woodpecker

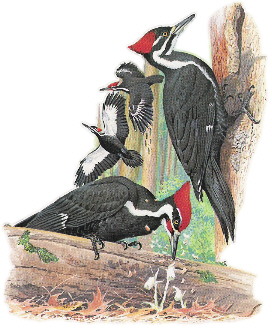

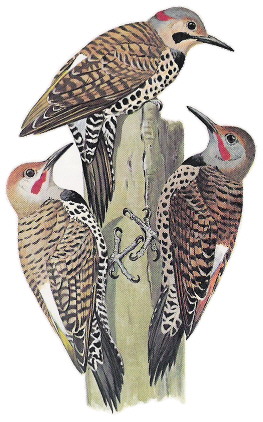

There are six types of woodpeckers common to the Kootenay region: the Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Three-toed Woodpecker, Black-backed Woodpecker, Pileated Woodpecker and the Northern Flicker.

Downy Woodpecker (Picoides Pubescens)

Length: 17 cm

A white back generally identifies both this woodpecker and the similar Hairy Woodpecker. The Downy Woodpecker is smaller in size, with a much smaller bill, their outer feathers generally have faint bars or spots. Birds in the Pacific Northwest have pale gray-brown back and underparts and birds living in the Rocky Mountains show less spotting on their wings; the females may be confused with the female Three-toed Woodpecker. Note the Downy’s conspicuous eyebrow and lack of barring on the sides. Calls include a soft pik note and a high whinny. They are quite common and often seen in backyard feeders, park lands and orchards, as well as forests.

Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides Villosus)

Length: 24 cm

A white back generally identifies both this woodpecker and the similar Downy Woodpecker. The Hairy Woodpecker is larger, with a much larger bill, their outer tail feathers are entirely white. Birds in the Pacific Northwest have pale gray-brown back and underparts. Rocky mountain birds have less spotting on their wings; the females are easily confused with the female Three-toed Woodpecker. Note the conspicuous eyebrow and lack of barring on back and flanks, sides are not barred. Its forehead is spotted with white, its crown is streaked with red or orange in young males. Its calls include a loud, sharp peek and slurred whinny. They inhabit dense mature forests and may move to open woods in the winter.

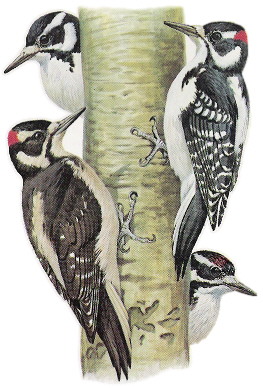

Three-Toed Woodpecker (Picoides Tridactylus)

Length: 22 cm

Black-and-white barring down the center of the back distinguishes the Three-toed Woodpecker from the similar Black-backed Woodpecker. Both have heavily barred sides. The male’s yellow cap is more extensive in the Three-toed. Barring on the back varies from heavy and dense in the eastern form (picoides tridactylus bacatus), to lighter in the northwestern (picoides tridactylus fasciatus). In the rocky mountain subspecies (picoides tridactylus dorsalis), their backs may be mostly white rather than barred. Females resemble female Hairy or Downy Woodpeckers, look for heavily barred sides. Its call is a single pik. Three-toed Woodpeckers are found in coniferous forests, especially in burned-over areas.

Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides Arcticus)

Length: 24 cm

They have solid black back, heavily barred sides. Males have distinct yellow cap. Similar to the Three-toed Woodpecker, it has a barred back. The Black-backed Woodpecker inhabits coniferous forests and is often found in burned-over areas, foraging on dead conifers, flaking away large patches of loose bark rather than drilling into it, in search of larvae and insects. Its call note is a single, sharp kik. They are uncommon. In winter, it withdraws from the highest altitudes in northernmost part of range and may visit wooded valleys.

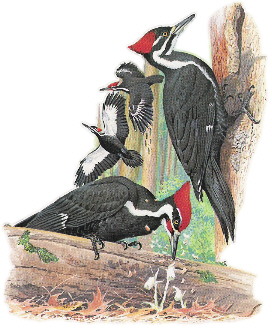

Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus Pileatus)

Length: 42 cm

A perched bird is almost entirely black on its back and wings. Pileated is the largest woodpecker commonly seen. The female’s red cap is less extensive than in the male. Juvenile plumage, held briefly, resembles the adult but is paler overall. Call is a loud, rising and falling wuck-a-wuck-a-wuck-a, similar to the flicker. They are generally uncommon and localized throughout much of its range. It prefers dense, mature forests but also seems to be adapting to human encroachment, becoming more common and more tolerant of disturbed habitats, especially in the east. Also found in woodlots and park lands, as well as deep woods. Listen for its slow, resounding hammering, look for the long rectangular or oval holes it excavates. Carpenter ants in fallen trees and stumps are its major food source.

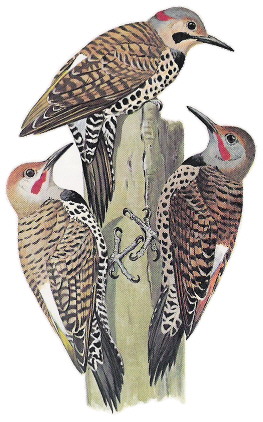

Northern Flicker (Colaptes Auratus)

Length: 32 cm

It has a brown barred back with spotted underparts and black crescent bib. Its white rump is conspicuous in flight and it lacks white wing patches. Females lack red or black whisker stripe. All three forms—yellow-shafted, red-shafted, and gilded flicker—are regularly seen in the Midwest and southwest. Large, active, and noisy, flickers are common in open woodlands and suburban areas, often feeding on the ground. Calls include a rapid wik-wik-wik-wik and wick-er, wick-er, wick-er, and a single, loud klee-yer.

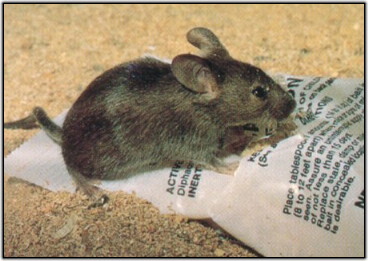

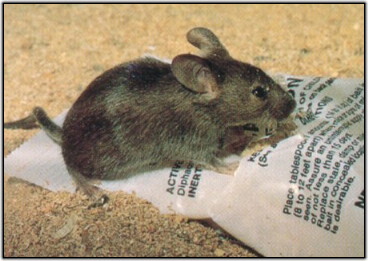

Deer Mouse

The Deer mouse is a small, white-footed mouse with large dark eyes and long whiskers. The soft fur of the deer mouse varies in colour from a golden brown to a pale grey on the back, while the underparts are white, including the underside of the relatively long tail. The ears are large, round and covered with fine hairs; they can be described as Mickey Mouse-like. Deer mice have four toes on the forefeet and five toes on the hind feet. Adult deer mice weigh from 10 to 35 grams with external measurements averaging 17 mm total length, 81 mm for the tail, 20 mm for the hind foot and ears measuring between twelve to 20 mm.

Habitat

Habitat

The Deer mouse is found throughout BC and indeed can be found all over North America particularly in forests, prairies, and deserts but not usually in urban area or where the ground is continually wet. Their natural habitat is rural and semi-rural areas where they inhabit fields, pastures and the various types of vegetation found around homes and outbuildings.

The Deer mouse builds a spherical nest by shredding materials such as bark, grass, hair, string and the fluff from cattails into a soft, warm bed with one main entrance. The nesting site can be found anywhere where there is a cavity or opening, such as under rocks, wood piles or in empty bird nests. Deer mice drop their scat and urinate in and around their nest site, posing the threat of Hantavirus whenever the Deer mouse is found in sheds, attics, feed bins or other enclosed spaces were people may breathe the dust from the nest.

Breeding

Breeding

Breeding starts very late in the winter and young are born in April; on average, the deer mouse has four litters each year. The gestation period varies from 22 to 27 days, averaging about 24 days.

Litter size ranges from one to nine, averaging about four. At birth the young are blind, pink, and hairless and weigh from 1.1 to 2.3 grams. The male, while not present at birth, does return to assist in the care of the young. Sexual maturity is reached before the young lose their “blue” juvenile pelage, and females born early in the year may themselves produce young by late summer or early fall.

The deer mouse is omnivorous and feeds on seeds, plant greens, berries, nuts, mushrooms, insects and carrion. They will also gnaw on bones or antlers for the calcium.

Deer mice in turn are an important food source for many carnivores like weasels, fox, skunks, minks, raccoons, bears, coyotes, and wolves. Owls and snakes are also important predators.

House Mouse

The house mouse is common in all parts of Canada. The house mouse is dusty grey in colour and measures from 10 to 15 cm long with large ears and small eyes. The tail is usually the same length as the mouse. The house mouse is sometimes confused with the deer mouse, which is pale grey to reddish brown in colour and has a bi-coloured tail with a white underside.

Mice are nibblers and thus tend to make small holes or other slight damage in many places rather than a lot of damage at one place. The house mouse has a keen sense of touch, smell and hearing. They can run, climb, jump and swim very well.

The house mouse is considered one of the major structural pests, causing serious economic loss, health hazards and unsanitary environments.

House mice eat the same food as humans, including cereals, seeds, fruits and vegetables and are especially fond of sweet liquids. Because they nibble, they may feed as often as 15 to 20 times each day consuming only a small amount of food each time.

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

The average lifespan of a mouse is 12 months. The young are born about 20 days after breeding and mature rapidly; a single female may have as many as eight litters per year, averaging five to six young each.

By three months, the young are independent and capable of reproduction. Mice can survive outdoors during the winter under certain conditions but generally invade buildings when the weather turns cold.

Habits and Health Hazards

Since the contributing factor to a mouse infestation is the presence of food, good housekeeping is essential. This includes the proper storage of foods in sealed jars or tins, in addition, all refuse should be stored in containers with tight-fitting lids.

Mice cause extensive damage to houses, granaries, restaurants, bakeries – any place food is handled or stored – they will gnaw through wood to gain entrance into buildings. In constructing their nests, mice will destroy fabrics and leather goods and can cause fires by chewing through the insulation on electrical wires.

Mice contaminate food with their droppings and urine. They spread such diseases as salmonella bacteria, lepospirae and typhus. As well, they carry parasites such as fleas, round worms and mites.

Mice are year-round pests with activity and indoor migration increasing as weather gets cooler. Mice become active primarily during the evening and remain so until the middle of the night but if food is scarce or the infestation is large, they will be active during daylight hours.

Mice nest in any safe location close to food, preferring the spaces in double walls, above ceilings and floors and closed-in areas around counters. There are several ways that mice make their existence known, droppings near available food is the most common indication. Noises made by their running, gnawing and scratching will provide clues to their actual location and holes gnawed in bags and boxes containing food or garbage is also a sign of mouse presence.

Pack Rat (Bushy-Tailed Wood Rat)

The bushy-tailed wood rat, otherwise locally known as the pack rat is the only native rat found in Canada. It is immediately distinguished from the introduced Norway and roof rats by its bushy tail.

It is a large, gentle, squirrel-like rodent. Its adult fur coat is long, soft, dense, usually grey on the back and with tawny brown sides. The undersides and feet are white.

Measurements of males are: total length, 280 to 460mm (11 to 18”), tail, 105 to 222mm (4 to 8.75”), weight, 211 to 526g (7.4 to 18.4oz.). Males are eight to 10% larger than females.

Wood rats are active all year and primarily solitary and nocturnal. They are most active during the first half hour after sunset and dawn. One individual to 20 acres is an average density in its preferred habitat. Their presence is characterized by their large bulky residence composed of twigs, bones, foliage, debris and all manner of human artifacts, some containing up to three bushels of material. Their actual nest is sited in the centre of this mound, and is made of shredded bark, grass and moss—and if in human environments, soft, shredded cloth, cotton batting, wool, etc. The nest itself is tidy but nearby are the toilet areas, where the waste encrusts and stains and cements loose debris to the rocks.

For food, they prefer the leaves of aspen, willows, roses, cherries, currants, snowberries and elderberries, but will also eat the twigs and needles of Douglas-fir, Alpine Fir, Englemann Spruce and Junipers. They also use the seeds and fruit of Douglas-fir, anemones, gooseberries, cinquefoils, raspberries, fireweed, gentians, elderberries, honeysuckles and goldenrod. In autumn, they are provident, collecting and curing the available food items, and stockpiling them in crevices and under large boulders for their winter needs.

Beginning in February, the male meet up with a female and pursues her until they mate in March. The gestation period is 27 to 32 days. After the young are born, the female, who is dominant, drives out the male. The litter size is one to six (average three and a half). Under favourable conditions, two litters, about two months apart, are produced, but in the northern part of its range, usually only one. The young are weaned at age 26 to 30 days and reach maturity when about eleven months old.

Distribution within British Columbia

Most literature reports that the bushy-tailed wood rat is found throughout all of BC’s mainland and is absent from the coastal islands Some authors, however, report that this rodent is also absent from the northeast and northwest corners of the province. It is however very predominant in the Kootenay Region.

This rodent is not considered to be in jeopardy and is, therefore, not protected (Stevens and Lofts 1988).

Habitat Requirements

The bushy-tailed wood rat requires habitat that offers good security cover. Activity is significantly higher in areas that have 75 to 100% cover than in areas with less cover. The cover provided within rocky habitats such as talus slopes, caves, cliffs, river canyons, and rock outcrops in open forests appear to be favorite habitats for this wood rat. In the absence of rocky habitat, security cover can be provided by logging slash, hollow logs, abandoned buildings and mine shafts.

Wood rat habitats provide wood rats with suitable sites for building their stick “houses”. Wood rats owe their other common name of pack rat to their association with stick houses, which are generally quite large (one to 1.8m in height) and built out of woody debris, dried vegetation, and other objects the wood rat can collect, including human artifacts such as silverware, jewelry and clothing. These houses are preferably situated within the shelter of a rocky overhang, but can sometimes be found in the open, up a tree, or in the attic space of your home

Although they are often referred to as houses, the piles of debris created by wood rats do not often function as shelters and wood rats do not usually reside therein. Large wood rat piles function more as a storage dump than a house. Their true nests are small (about 15cm in diameter), cup-shaped, and are made up of finely shredded bark and other soft materials such as fur. These nests may be found within the larger stick house, but are more commonly found in a sheltered spot nearby.

Food Habits

The wood rat is an omnivorous rodent that will make a meal out of a variety of plants, insects, small amphibians, and carrion. The majority of the wood rat’s diet is comprised of green and dry vegetation. Preference is shown for the foliage of herbs, shrubs, and trees, but not grasses. They also feed on the vascular tissues of Douglas-fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock. Willow leaves are also a favoured food. Bushy-tailed wood rats stockpile large quantities of dried vegetation to sustain them throughout the winter months.

Daily Activity and Movement Patterns

Daily Activity and Movement Patterns

The bushy-tailed wood rat is nocturnal in activity, but can be observed occasionally during the day. They will rarely venture far from the nest. Although the bushy-tailed wood rat can climb trees, and will occasionally locate its stick house up a tree, it is less arboreal than its semi-arboreal cousin, the dusky-footed wood rat.

Bushy-tailed wood rats are a solitary species that defend territories. Males spend considerable time marking their territory with their ventral musk glands, which they rub on toilet posts, food caches, and nests. This can also create a very recognizable odour when found nesting inside your home.

Seasonal Activities and Movement Patterns

The bushy-tailed wood rat does not hibernate; instead it actively prepares for the winter by stockpiling a cache of vegetation, which it gathers and dries in the sun during the growing season. Winter months are primarily spent below the snow among the cover provided by their rocky habitat, however, short trips may be made over the snow’s surface.

Wood rats remain solitary, except during the breeding season, which in BC begins in late March and lasts until late May. After a gestation period of 27 to 32 days females give birth to an average of four young (range of one to six) during early May to late June. Several authors report that the bushy-tailed wood rat has multiple litters per year. However within BC, the wood rat is commonly reported as having only a single litter per year.

Bushy-tailed wood rats do not travel significant distances throughout the year (with perhaps the exception of dispersing juveniles), remaining in the near vicinity of their stick houses and nesting sites.

Physical Signs

Good indicators of bushy-tailed wood rat presence are the deposits of urine and feces that accumulate within this animal’s home range. Feces and urine can form a thick tar-like substance (often mistaken for some kind of mineral), if deposited in a spot sheltered from the rain, such as within a cave or under a rock overhang. Bright white streaks result from urine deposited on rocks not sheltered from the rain. The rain is thought to leach out the organic components of the urine leaving a white calcareous deposit behind. These white deposits are useful sign to look for when sampling for bushy-tailed wood rats, as they can be observed from a distance and are often indicative of occupation (or former occupation) of an area by a wood rat.

Because feces and urine deposits are very persistent, lasting for thousands of years in sheltered areas such as caves, and decades on exposed surfaces such as cliffs, care must be taken not to confuse past use of a site with that of current use. Simply locating fresh streaks of urine can quickly answer this question. Fresh urine can be recognized by its transparent yellow to opaque brown colour, skunky odour and stickiness.

Stick Houses

Bushy-tailed wood rats are or have recently been present in a study area if an investigator discovers the large stick “houses” used by this wood rat. These structures, made primarily out of woody material and a variety of other debris, are often located in a sheltered area such as a cave, under a rock ledge, within an abandoned building, around the base of a tree or log, inside a hollow snag, or sometimes even up a tree. Although wood rat “houses” are usually not placed in the open, because of their large size (0.9 to 1.8m), they can usually be spotted with relative ease.

Damage Caused by Feeding and Construction

Because the bushy-tailed wood rat is an animal that feeds on a large variety of plants within its home range, clipped shoots and branches, with the usual oblique cut common to most rodent feeding scars, are possible indicators of wood rat presence. However, such feeding sign is difficult to distinguish from other rodent feeding damage. A less ambiguous sign produced by this wood rat are the patches of bark removed from the boles of trees for nest construction. From a distance, this debarking may be confused with that of the porcupine or tree squirrels. Unlike the tree squirrels that discard the bark and feed on the exposed sapwood, the bushy-tailed wood rat transports all of the removed bark to its nest for construction. Therefore, there will be no discarded strips of bark found beneath the trees damaged by bushy-tailed wood rats, as there would beneath trees damaged by tree squirrels or porcupines. In addition, wood rats do not feed on the sapwood, rather they just remove the outer bark (often the sapwood is not even exposed), whereas, porcupine and tree squirrel feeding will always expose the sapwood.

Skunk

Skunks are legendary for their powerful predator-deterrent—a hard-to-remove, horrible-smelling spray. A skunk’s spray is an oily liquid produced by glands under its large tail. To employ this scent bomb, a skunk turns around and blasts its foe with a foul mist that can travel as far as 10 feet (three metres).

Skunk spray causes no real damage to its victims, but it sure makes them uncomfortable. It can linger for many days and defy attempts to remove it. As a defensive technique, the spray is very effective. Predators typically give skunks a wide berth unless little other food is available.

Identification and Habitat

Identification and Habitat

There are many different kinds of skunks. They vary in size (most are housecat-sized) and appear in a variety of striped, spotted, and swirled patterns—but all are a vivid black-and-white that makes them easily identifiable and may alert predators to their pungent potential.

Skunks usually nest in burrows constructed by other animals, but they also live in hollow logs or even abandoned buildings. In colder climates, some skunks may sleep in these nests for several weeks of the chilliest season. Each female gives birth to between two and ten young each year.

Skunks are opportunistic eaters with a varied diet. They are nocturnal foragers who eat fruit and plants, insects, larvae, worms, eggs, reptiles, small mammals, and even fish. Nearly all skunks live in the Americas, except for the Asian stink badgers that have recently been added to the skunk family.

Pigeon

Origins

Origins

Pigeons and doves have been around for a long time—long before humans. Rock doves are thought to have originated in southern Asia several million years ago. Compare this to modern humans that first appeared about 120,000 years ago.

Size and Weight

A pigeon is about 13” (32cm) in length from bill to tail and weighs a little less than a pound (0.35 kg). Males are slightly bigger than females.

A pigeon family:

- Hen: an adult female pigeon

- Cock: an adult male pigeon

- Hatchling: a newly hatched pigeon just a few days old

- Squab: a young pigeon from one to 30 days old. When ready to leave its nest, a squab can sometimes weigh more than its parents.

- Peeper or Squeaker: a young bird that is learning to eat

- Fledgling: a bird that is ready to fly or that has just taken its first flight

- Juvenile: a bird out of its nest and flying but less than eight months old

- Nest and roosting sites: A pigeon nest usually is constructed on covered building ledges that resemble cliffs, a rock dove’s natural habitat. They also nest and roost on the support structures under bridges in cities and along highways.

Nesting

A pigeon nest usually is constructed on covered building ledges that resemble cliffs, a rock dove’s natural habitat. They also nest and roost on the support structures under bridges in cities and along highways. Pigeons build their nests with small twigs. A cock brings the nesting material to his mate, one piece at a time, and she builds the nest. Nests are usually well-hidden and hard to find.

Breeding

Pigeons usually lay two white eggs. The parents take turns keeping their eggs warm (incubating). Males usually stay on the nest during the day; females, at night. Eggs take about 18 days to hatch. Both male and female parent pigeons produce a special substance called “pigeon milk”, which they feed to their hatchlings during their first week of life. Pigeon milk is made in a special part of the bird’s digestive system called the “crop”. When hatchlings are about one week old, the parents start regurgitating seeds with crop milk; eventually seeds replace the pigeon milk.

Colouring and Feathers

There may be as many as 28 pigeon colour types, called “morphs”. Pigeons also have colourful neck feathers. These iridescent green, yellow, and purple feathers are called “hackle”. Adult males and females look alike, but a male’s hackle is more iridescent than a female’s. White feathers are actually feathers that have no colour pigments. So, when you see white on pigeons you are actually seeing no colour.

Adults have orange or reddish orange eyes; juveniles that are less than six to eight months old have medium brown or grayish brown eyes. Pigeon legs and feet are red to pink to grayish black. Their claws are usually grayish black but can be white on some pigeons. Some birds have “stockings”, which are feathers on their legs and feet! The cere is the fleshy covering on the upper part of a pigeon’s beak. It is grayish in young birds or juveniles, and white in adults. Albino birds may have pinkish ceres.

Pigeons have many types of feathers, including contour feathers, the stiff feathers that give the body its shape, and down, the fluffy insulating feathers. Many pigeon feathers are accompanied by one or two filoplume feathers, which look like hairs. These filoplumes may have sensory functions, such as detecting touch and pressure changes.

Senses and Calls

Senses and Calls

Pigeon eyesight is excellent. Like humans, pigeons can see colour, but they also can see ultraviolet light—part of the light spectrum that humans can’t see. Pigeons are sometimes used in human search-and-rescue missions because of their exceptional vision.

Pigeons can hear sounds at much lower frequencies than humans can, such as wind blowing across buildings and mountains, distant thunderstorms, and even far-away volcanoes. Sensitive hearing may explain why pigeons sometimes fly away for no apparent reason: maybe they heard something you can’t.

Pigeons make two types of sounds: vocal (using voice) and non-vocal. The primary call used by males to attract mates and defend territories is coo roo-c’too-coo. From their nests they might say oh-oo-oor. When they are startled or scared they might make an alarm call like: oorhh! Pigeon babies make non-vocal sounds such as bill snapping and hissing. After mating, males often make clapping sounds with their wings.

Behaviour

Most birds take a sip of water and throw back their heads to let the water trickle down their throats. But pigeons (and all of their relatives in the family Columbidae) suck up water, using their beaks like straws.

Do pigeons have compasses in their heads? Not really, but pigeons, especially those bred for their homing instincts, seem to be able to detect the Earth’s magnetic fields. Cornell University pigeon researcher Dr. Charles Walcott says that magnetic sensitivity, along with an ability to tell direction by the sun, seems to help pigeons find their ways home.

On the ground, pigeons don’t hop the way many birds do. They walk or run with their heads bobbing back and forth. Pigeons are strong fliers and can fly up to 40 or 50 miles per hour. Some pigeons are raised for their exceptional abilities to fly fast and find their ways home. These pigeons may fly as far as 600 miles in a day. Although feral pigeons are good fliers too, most of these birds seem to stay close to their regular feeding sites.

Natural Predators

Natural Predators

One species of falcon, Merlin, eats so many pigeons its scientific name is Falco columbarius (with the “columba-” meaning pigeon) and it was formerly called pigeon hawk. Merlins are medium-sized falcons and although they are not very common in cities, you can bet they are preying on pigeons living in open parks near marshes and ponds. In cities where peregrine falcons have become established, they catch and eat feral pigeons, often carrying them back to feed to their nestlings. Red-tailed and Cooper’s hawks also prey on pigeons in cities and in rural areas.

Fancy Pigeons

People raise all kinds of fancy pigeons. The breeds have names, such as rollers, tumblers, and fantails, which reflect the way the birds fly or the way they look. Sometimes, people take their fancy pigeons to compete in shows.

Sow bugs are land crustaceans and look very similar to pill bugs, at least at first glance. Sow bugs are small crustaceans with oval bodies when viewed from above, their back consists of a number of overlapping, articulating plates. They have seven pairs of legs, and antennae which reach about half the body length. Most are slate gray in colour and may reach 15 mm long and 8 mm wide.

The pill bug on the other hand has a rounder back from side to side, and a deeper body from back to legs. When disturbed, it frequently rolls into a tight ball with its legs tucked inside, much like its larger but dissimilar counterpart, the armadillo.

Sow bugs are land crustaceans and look very similar to pill bugs, at least at first glance. Sow bugs are small crustaceans with oval bodies when viewed from above, their back consists of a number of overlapping, articulating plates. They have seven pairs of legs, and antennae which reach about half the body length. Most are slate gray in colour and may reach 15 mm long and 8 mm wide.

The pill bug on the other hand has a rounder back from side to side, and a deeper body from back to legs. When disturbed, it frequently rolls into a tight ball with its legs tucked inside, much like its larger but dissimilar counterpart, the armadillo.

Control

The presence of sow bugs or pill bugs in the living quarters of a home is an indication of high-moisture conditions. This condition will also contribute to a number of other problems including mildew, wood rot and a good breeding environment for other insects. Reduce moisture or humidity level indoors. Use bathroom fans, stove hood vent fans, vent clothes dryers outside. Crawl spaces and attics need to be well ventilated. Remove excess vegetation and debris around exterior perimeter of the home. Make sure that leaf debris (leaves hold moisture and hide the bugs) is cleaned up from around the outside of your house. Keep rain gutters and downspouts clean and in good repair. Instead of chemicals, use caulking to close any cracks or crevices at or near ground level.

Control

The presence of sow bugs or pill bugs in the living quarters of a home is an indication of high-moisture conditions. This condition will also contribute to a number of other problems including mildew, wood rot and a good breeding environment for other insects. Reduce moisture or humidity level indoors. Use bathroom fans, stove hood vent fans, vent clothes dryers outside. Crawl spaces and attics need to be well ventilated. Remove excess vegetation and debris around exterior perimeter of the home. Make sure that leaf debris (leaves hold moisture and hide the bugs) is cleaned up from around the outside of your house. Keep rain gutters and downspouts clean and in good repair. Instead of chemicals, use caulking to close any cracks or crevices at or near ground level.

Root weevils are common invaders of Kootenay homes. Although a nuisance, they cause no harm to humans, pets or household furnishings.

Life Cycle and Habits

The black vine and strawberry root weevil have similar life cycles and are the most common in BC.

Root weevils wander into homes most frequently during late June and July. Household migrations greatly increase during periods of hot, dry weather. The insects apparently are attracted to the moisture of the building. Inside homes, the root weevils cause no injury to humans or household furnishings, they can, however, be quite abundant and a considerable nuisance.

Root weevils are common invaders of Kootenay homes. Although a nuisance, they cause no harm to humans, pets or household furnishings.

Life Cycle and Habits

The black vine and strawberry root weevil have similar life cycles and are the most common in BC.

Root weevils wander into homes most frequently during late June and July. Household migrations greatly increase during periods of hot, dry weather. The insects apparently are attracted to the moisture of the building. Inside homes, the root weevils cause no injury to humans or household furnishings, they can, however, be quite abundant and a considerable nuisance.

Control

Because root weevils do no harm inside homes, the best way to handle infestations is to tolerate occasional beetles, vacuuming them as they are observed. However, if greater numbers are observed, a treatment can reduce the amount of activity. For more information regarding a treatment, please call us anytime.

Control also includes sealing openings and screening windows to prevent entry. Root weevil populations can be reduced by removing plants around the outside of the home on which the insects feed. These especially include Rhododendrons and Yews (or Taxus). Reducing watering around building foundations may limit root weevil migrations, as the adult insects appear attracted to shade and moisture.

Control

Because root weevils do no harm inside homes, the best way to handle infestations is to tolerate occasional beetles, vacuuming them as they are observed. However, if greater numbers are observed, a treatment can reduce the amount of activity. For more information regarding a treatment, please call us anytime.

Control also includes sealing openings and screening windows to prevent entry. Root weevil populations can be reduced by removing plants around the outside of the home on which the insects feed. These especially include Rhododendrons and Yews (or Taxus). Reducing watering around building foundations may limit root weevil migrations, as the adult insects appear attracted to shade and moisture.

Black Vine Weevil

One of several types of root feeding weevils, the black vine weevil is the most destructive and widespread. A European native, it was most likely introduced accidentally in plant materials. Though first reported in 1910 in Connecticut, researchers suspect that it was introduced in the 1830s.

This weevil has spread by the movement of ornamental plants and thus is found throughout most of Canada. Facilitating its wide geographic range may be its rather flexible choice of foods—it feeds on over 100 types of plants, trees, shrubs and flowers.

Black Vine Weevil

One of several types of root feeding weevils, the black vine weevil is the most destructive and widespread. A European native, it was most likely introduced accidentally in plant materials. Though first reported in 1910 in Connecticut, researchers suspect that it was introduced in the 1830s.

This weevil has spread by the movement of ornamental plants and thus is found throughout most of Canada. Facilitating its wide geographic range may be its rather flexible choice of foods—it feeds on over 100 types of plants, trees, shrubs and flowers.

Although the cluster fly is a nuisance pest for homeowners, they do not bite people, carry diseases, nor cause any real damage to a home. Cluster flies are about five-sixteenths of an inch long; they are gray with golden-toned hairs on their thorax.

Spotting them is easy because they are usually clustered together sunning themselves on exterior walls. This is also where their name comes from because when resting, they generally cluster together.

The cluster flies are similar to many other pests as they want to get inside houses to stay warm. With this in mind, the winter is when people will most often find cluster flies inside their homes.

Although the cluster fly is a nuisance pest for homeowners, they do not bite people, carry diseases, nor cause any real damage to a home. Cluster flies are about five-sixteenths of an inch long; they are gray with golden-toned hairs on their thorax.

Spotting them is easy because they are usually clustered together sunning themselves on exterior walls. This is also where their name comes from because when resting, they generally cluster together.

The cluster flies are similar to many other pests as they want to get inside houses to stay warm. With this in mind, the winter is when people will most often find cluster flies inside their homes.

Habits and Breeding

Cluster flies search for any small openings that will get them into a house; open windows or doors are great opportunity. They generally enter homes in the fall, as the weather begins to cool down.

By winter, most cluster flies will be hibernating within a warm home. While hibernating the cluster fly is not very active, so a homeowner might not even know they are there – although there are occasions where the cluster flies will come out in to sun themselves – a lovely, warm and south facing window is where a homeowner is likely to spot them, otherwise they pretty much stay in hibernation.

Also known as an attic fly, Cluster flies like to hibernate in – you guessed it – attics and wall voids. They like to be higher off the ground and will cluster together once in hibernation.

Habits and Breeding

Cluster flies search for any small openings that will get them into a house; open windows or doors are great opportunity. They generally enter homes in the fall, as the weather begins to cool down.

By winter, most cluster flies will be hibernating within a warm home. While hibernating the cluster fly is not very active, so a homeowner might not even know they are there – although there are occasions where the cluster flies will come out in to sun themselves – a lovely, warm and south facing window is where a homeowner is likely to spot them, otherwise they pretty much stay in hibernation.

Also known as an attic fly, Cluster flies like to hibernate in – you guessed it – attics and wall voids. They like to be higher off the ground and will cluster together once in hibernation.  Once spring starts, the cluster flies will leave the house and venture back outside where they will mate and eat, neither of which they do during hibernation.

The cluster fly reproduces frequently. Females don’t to do much: once they have mated they lay their eggs in soil near earthworms. About three days later the eggs will hatch and the larvae will migrate towards the earthworms, burrowing inside and using the earthworm as a food source. Once fully developed, the cluster fly will be on its own. This cycle will continue from the spring to the summer, during which four generations or more can be made. As summer comes to an end and fall approaches the cluster flies begin to look for another home, or the same home, to hibernate in.

Once spring starts, the cluster flies will leave the house and venture back outside where they will mate and eat, neither of which they do during hibernation.

The cluster fly reproduces frequently. Females don’t to do much: once they have mated they lay their eggs in soil near earthworms. About three days later the eggs will hatch and the larvae will migrate towards the earthworms, burrowing inside and using the earthworm as a food source. Once fully developed, the cluster fly will be on its own. This cycle will continue from the spring to the summer, during which four generations or more can be made. As summer comes to an end and fall approaches the cluster flies begin to look for another home, or the same home, to hibernate in.

Habits

Earwigs forage mainly at night, and during the day conceal themselves in all sorts of enclosed spaces: under stones, wood and bark, in vegetation and flowers. Even those species able to fly seldom seem to do so.

The 1350 species of earwigs in the nine families of the Order Dermaptera are mostly tropical in distribution. Some species are native in temperate regions, but few can tolerate cold winters and all the species recorded in BC were introduced from other lands. The random, alien origin of our earwigs is reflected in the diversity of the small fauna – four species in four genera and three families. Like cockroaches, earwigs are secretive and omnivorous, two characteristics that make them successful hitchhikers with human travelers – some kinds have become cosmopolitan.

Habits

Earwigs forage mainly at night, and during the day conceal themselves in all sorts of enclosed spaces: under stones, wood and bark, in vegetation and flowers. Even those species able to fly seldom seem to do so.

The 1350 species of earwigs in the nine families of the Order Dermaptera are mostly tropical in distribution. Some species are native in temperate regions, but few can tolerate cold winters and all the species recorded in BC were introduced from other lands. The random, alien origin of our earwigs is reflected in the diversity of the small fauna – four species in four genera and three families. Like cockroaches, earwigs are secretive and omnivorous, two characteristics that make them successful hitchhikers with human travelers – some kinds have become cosmopolitan.

Unlike cockroaches, most of these successful immigrants have established themselves out-of-doors and are not normally pests of human habitations. In Canada, because of their foreign origins and dislike of the cold, most species are concentrated on the coasts and in the Great Lakes region. They tend to live in disturbed habitats, on beaches and around gardens and human habitations.

Most species are omnivorous scavengers although some are known to be exclusively predaceous; in coastal BC for example, Anisolabis maritima (Bonelli) evidently feeds mainly on invertebrates found on ocean beaches. Forficula auricularia Linnaeus, when abundant, can be a pest of garden plants, and is especially fond of flowers. In general, earwigs probably cause serious damage to plants only when insect prey is limited. Prey can be captured with the forceps, although these are also used in courtship and probably mostly in defence: the larger species can give a human finger a painful pinch.

Eggs are laid in underground burrows, usually in batches of 20 to 40. Females of some species, including the widespread Forficula auricularia, guard the eggs and show some care and protection of their young. Family groups often remain associated and semisocial behaviour occurs. Nymphs usually moult four to six times.

Description

The earwig body is small- to moderately-sized (5 to 30 mm long, although some foreign species may reach 5 cm), slender, elongated and rather flattened. The mouth parts are made for chewing and the antennae are filamentous, usually less than half the body length. There are no ocelli. Legs are similar in size and form; the tarsi have three segments. Wings are often absent. When present, the forewings are modified into short, rectangular, vein-less, leathery flaps. Hind wings may be absent even if the forewings are developed, but when present, are usually semicircular and pleated, with radiating veins. Each is stowed as a folded packet under the much smaller forewings, and the tips often project from beneath. The paired cerci at the tip of the abdomen are usually unsegmented, and strongly sclerotized into forceps. These pincers, which are the most familiar feature of the order, are usually stronger and more curved in males. The females, except in some primitive species, lack an ovipositor.

To control the number of earwigs in and around the house:

Unlike cockroaches, most of these successful immigrants have established themselves out-of-doors and are not normally pests of human habitations. In Canada, because of their foreign origins and dislike of the cold, most species are concentrated on the coasts and in the Great Lakes region. They tend to live in disturbed habitats, on beaches and around gardens and human habitations.

Most species are omnivorous scavengers although some are known to be exclusively predaceous; in coastal BC for example, Anisolabis maritima (Bonelli) evidently feeds mainly on invertebrates found on ocean beaches. Forficula auricularia Linnaeus, when abundant, can be a pest of garden plants, and is especially fond of flowers. In general, earwigs probably cause serious damage to plants only when insect prey is limited. Prey can be captured with the forceps, although these are also used in courtship and probably mostly in defence: the larger species can give a human finger a painful pinch.

Eggs are laid in underground burrows, usually in batches of 20 to 40. Females of some species, including the widespread Forficula auricularia, guard the eggs and show some care and protection of their young. Family groups often remain associated and semisocial behaviour occurs. Nymphs usually moult four to six times.

Description

The earwig body is small- to moderately-sized (5 to 30 mm long, although some foreign species may reach 5 cm), slender, elongated and rather flattened. The mouth parts are made for chewing and the antennae are filamentous, usually less than half the body length. There are no ocelli. Legs are similar in size and form; the tarsi have three segments. Wings are often absent. When present, the forewings are modified into short, rectangular, vein-less, leathery flaps. Hind wings may be absent even if the forewings are developed, but when present, are usually semicircular and pleated, with radiating veins. Each is stowed as a folded packet under the much smaller forewings, and the tips often project from beneath. The paired cerci at the tip of the abdomen are usually unsegmented, and strongly sclerotized into forceps. These pincers, which are the most familiar feature of the order, are usually stronger and more curved in males. The females, except in some primitive species, lack an ovipositor.

To control the number of earwigs in and around the house:

Tegenaria Agrestis, better known as the hobo spider, is a recently introduced species to the United States and Canada, coming from Europe to the Pacific Northwest.

Hobo spiders have been labeled as spiders of medical importance because of the belief that their bites can cause severe pain and potentially necrotic wounds. The research, however, on hobo spider bites is incomplete with no definitive answer regarding their level of danger to humans.

Most experts warn against using a single picture for any conclusive spider identification, including the hobo. Given that fact, the picture here shows a spider that has many of the hobo spider’s physical characteristics. There are no bands on the legs and the abdomen has a “v” pattern down the middle.

Compare the picture to the left with the picture below of the giant house spider, another Tegenaria species. The slight differences in the colour of the abdomen and cephalothorax provide another comparative identification clue.

Tegenaria Agrestis, better known as the hobo spider, is a recently introduced species to the United States and Canada, coming from Europe to the Pacific Northwest.

Hobo spiders have been labeled as spiders of medical importance because of the belief that their bites can cause severe pain and potentially necrotic wounds. The research, however, on hobo spider bites is incomplete with no definitive answer regarding their level of danger to humans.

Most experts warn against using a single picture for any conclusive spider identification, including the hobo. Given that fact, the picture here shows a spider that has many of the hobo spider’s physical characteristics. There are no bands on the legs and the abdomen has a “v” pattern down the middle.

Compare the picture to the left with the picture below of the giant house spider, another Tegenaria species. The slight differences in the colour of the abdomen and cephalothorax provide another comparative identification clue.

The hobo spider belongs to the funnel web spider family (Agelenidae), the two spinnerets extending from the bottom of the abdomen being characteristic of the species.

Like other funnel web spiders, they prefer the outdoors and tend to only come indoors during the late fall, as the season changes. Wandering males also are known to meander through a house.

Persons suspecting they have been bitten by a hobo spider should seek medical attention. If circumstances permit, trapping the spider for positive identification helps with diagnosis and treatment.

The hobo spider belongs to the funnel web spider family (Agelenidae), the two spinnerets extending from the bottom of the abdomen being characteristic of the species.

Like other funnel web spiders, they prefer the outdoors and tend to only come indoors during the late fall, as the season changes. Wandering males also are known to meander through a house.

Persons suspecting they have been bitten by a hobo spider should seek medical attention. If circumstances permit, trapping the spider for positive identification helps with diagnosis and treatment.

The three species look very similar, with the hobo spider commonly considered a species of medical concern. The range of the hobo spider and giant house spider are limited mainly to the Pacific Northwest, although extended ranges to Utah, Montana and the interior BC are reported.

While giant house spiders are large, up to 3” long with their legs extended, their bites are not as dangerous as the hobo spider. In fact, they are a natural predator of the hobo spider and their presence is considered a natural pest management remedy.

The three species look very similar, with the hobo spider commonly considered a species of medical concern. The range of the hobo spider and giant house spider are limited mainly to the Pacific Northwest, although extended ranges to Utah, Montana and the interior BC are reported.

While giant house spiders are large, up to 3” long with their legs extended, their bites are not as dangerous as the hobo spider. In fact, they are a natural predator of the hobo spider and their presence is considered a natural pest management remedy.

The Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella (Hubner), is one of the most commonly reported pests of stored grains in Canada.

Larvae of the Indian meal moth feed upon grains, grain products, dried fruits, nuts, cereals and a variety of processed food products. The Indian meal moth is also a common pantry pest.

The Indian meal moth is handsome with a wing expanse of nearly three-quarters of an inch. It is easy to distinguish from other grain pests by the peculiar markings of the forewings: they are reddish brown with a copper luster on the outer two-thirds and whitish gray on the inner, or body ends. The hind wings lack distinctive markings and are more or less uniformly gray. Adults can be seen resting on the grain surface or grain bin walls. The adults fly at night and are attracted to lights.

The Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella (Hubner), is one of the most commonly reported pests of stored grains in Canada.

Larvae of the Indian meal moth feed upon grains, grain products, dried fruits, nuts, cereals and a variety of processed food products. The Indian meal moth is also a common pantry pest.

The Indian meal moth is handsome with a wing expanse of nearly three-quarters of an inch. It is easy to distinguish from other grain pests by the peculiar markings of the forewings: they are reddish brown with a copper luster on the outer two-thirds and whitish gray on the inner, or body ends. The hind wings lack distinctive markings and are more or less uniformly gray. Adults can be seen resting on the grain surface or grain bin walls. The adults fly at night and are attracted to lights.

The eggs of the Indian meal moth are whitish, ovate and very small. making them difficult to see without the aid of a microscope.

The eggs of the Indian meal moth are whitish, ovate and very small. making them difficult to see without the aid of a microscope.  Newly hatched larvae are also very small and difficult to see. Larger larvae are usually yellowish, greenish or pinkish in colour. Fully grown larvae are a half to five-eighths of an inch in length with a brownish head capsule. Larvae have three sets of legs near the head (thoracic legs) and five sets of prolegs on the abdomen. Larvae of the meal moth spin a web as they become fully grown and leave behind silken threads wherever they crawl. This loosely clinging webbing on the grain is characteristic of this pest and often abundant enough to attract attention.

Newly hatched larvae are also very small and difficult to see. Larger larvae are usually yellowish, greenish or pinkish in colour. Fully grown larvae are a half to five-eighths of an inch in length with a brownish head capsule. Larvae have three sets of legs near the head (thoracic legs) and five sets of prolegs on the abdomen. Larvae of the meal moth spin a web as they become fully grown and leave behind silken threads wherever they crawl. This loosely clinging webbing on the grain is characteristic of this pest and often abundant enough to attract attention.

Life Cycle

As long as the temperature within a grain bin or building where grain is stored remains above 50° F (10° C), the Indian meal moth can survive and reproduce. A typical life cycle (egg to adult) is completed in forty to 55 days with the potential for seven to nine generations per year, however, because of cooler temperatures during the winter months, fewer generations are produced. Under optimal conditions, the entire life cycle can be completed in approximately 28 days.

A mature female lays 100 to 300 eggs on food material, either singularly or in groups of twelve to thirty. Larvae begin to hatch in two to fourteen days, depending on environmental conditions. Newly hatched larvae feed on fine materials within the grain and are small enough to pass through a 60-mesh screen making it difficult to exclude larvae from most packaged foods and grain.

Life Cycle

As long as the temperature within a grain bin or building where grain is stored remains above 50° F (10° C), the Indian meal moth can survive and reproduce. A typical life cycle (egg to adult) is completed in forty to 55 days with the potential for seven to nine generations per year, however, because of cooler temperatures during the winter months, fewer generations are produced. Under optimal conditions, the entire life cycle can be completed in approximately 28 days.

A mature female lays 100 to 300 eggs on food material, either singularly or in groups of twelve to thirty. Larvae begin to hatch in two to fourteen days, depending on environmental conditions. Newly hatched larvae feed on fine materials within the grain and are small enough to pass through a 60-mesh screen making it difficult to exclude larvae from most packaged foods and grain.